Located on the eastern flanks of the Highwood Mountains of Central Montana is the sprawling Strand Ranch, home to one of the last big working cattle operations in the state. Set on 30,000 contiguous acres — half of which are protected in a conservation easement through the Montana Land Reliance — the operation offers a case study in blending age-old ranching practices with a community-oriented conservationist ethic. And it also serves as a success story that features a savvy businessman, and also one who was dedicated to protecting the land that he loved.

THE LEGACY OF LEROY STRAND

Approximately 20 miles east of Great Falls, and separated from the main Rocky Mountain range that lies 70 miles to the west, the Highwoods are themselves somewhat unusual. Rising up from the surrounding ocean of prairie known as the Great Plains, they are what geologists refer to as an island range. The highest peak, Highwood Baldy, is not especially high — a little under 8,000 feet — but between Lewistown and Great Falls, the range provides the most significant alpine relief on the far-reaching horizon of ranch- and farmland in Central Montana.

THE 30,000-PLUS-ACRE STRAND RANCH, AT THE FOOTHILLS OF THE HIGHWOOD MOUNTAIN RANGE EAST OF GREAT FALLS, IS ONE OF THE LARGEST CONTIGUOUS CATTLE RANCHES IN CENTRAL MONTANA.

The story of the Strand Ranch centers on the legacy left by one of its chief namesakes, Leroy Strand. Though the ranch as it exists today was cobbled together by different owners over more than half a century, in 1964 Strand became the sole owner of one of the best-run and most-profitable cattle operations in Montana.

The ranch originated in the 1860s when Henry Macdonald, a 17-year-old Civil War veteran, made his way west by wagon train and steamboat to Judith Basin County. He eventually migrated further west into the Highwood Mountains, where he ran sheep and cows in the meadows, improvised a crude irrigation system, and dramatically developed the raw ground into agricultural land.

LEROY STRAND [1919-2016] RAN WHAT WAS KNOWN AS ONE OF THE MOST EFFICIENT AND MOST PROFITABLE CATTLE OPERATIONS IN THE STATE.

According to the ranch’s history, which Leroy Strand set down in a book titled From the Shellrock to the Highwoods when he was in his 90s, Macdonald eventually sold his holdings, even though he didn’t actually own any of the lands he had worked and developed. “All he had to sell were his squatter’s rights to graze livestock on the public domain, and his improvements, and his sheep,” Strand wrote; this was a common method of land acquisition in the second half of the 19th century in Montana.

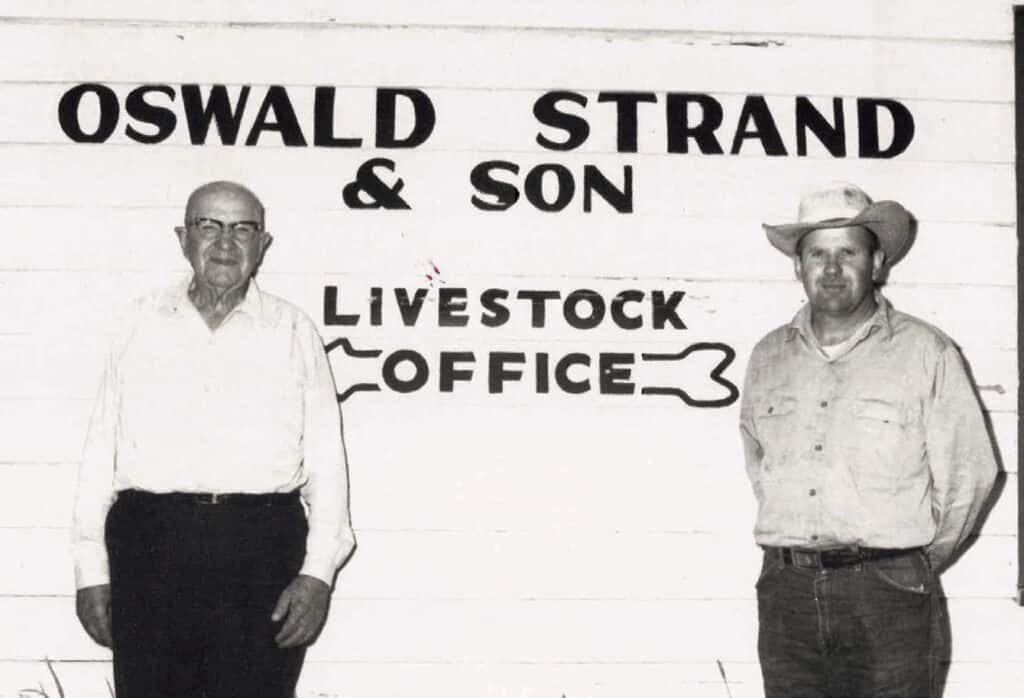

Macdonald sold his squatter’s rights and sheep operation to a pair of buyers from Maine, Isaac Libby and Charles Merrill, who started consolidating the land into deeded property by buying up homesteads belonging to those who had settled in the area after the Homestead Act of 1862. Following in their footsteps, Ole Osnes, a Norwegian immigrant, bought their land and continued to acquire various small farms and ranches in the area, consolidating them into a single parcel. In 1944, he sold the lands that now compose the Strand Ranch to Oswald Strand, a prominent cattle buyer from Iowa, who then owned it along with his wife Maude, and their two sons, Leroy and Dean. By 1957, Dean branched off and purchased the Sullivan Ranch, also in Central Montana, and in 1964, Leroy purchased the Strand Ranch from their father.

|

|

In addition to being a well-respected and accomplished cattleman, Leroy Strand built a reputation as a generous philanthropist, donating large sums to the C.M. Russell Museum and Benefis Cancer Center in Great Falls, to name just two beneficiaries of his largesse. In accordance with his spirit of community investment and interest in conservation around the Highwoods, Strand also started the Leroy and Claris Strand Foundation in 1998, and arranged to bequeath the entire ranch and the cattle operation to the foundation in his will. As part of that legacy, he also struck a deal with the Montana Land Reliance to preserve half of the acreage with a conservation easement. In comments to the Great Falls Tribune in 2001, Strand deplored the way the once-rich ranchlands of the Bitterroot Valley had been developed. “I want to keep mine as an operating ranch,” he said.

Strand died in 2016, and now the ranch is for sale for the first time since 1944, meaning the future of this legacy is up in the air per se. “Every year, the foundation is compelled by both federal law and the articles of the foundation to pay 5 percent of the fair market value of the assets to qualified charities,” says Gary Bjelland, an attorney for the Strand Foundation. “In this case, that means that the recipients of foundation grants must be in the local community; that is, right around Geyser, Montana.” Bjelland notes that when the ranch sells, all of the proceeds would go into the foundation, creating a permanent endowment for that charity distribution. “For the sake of the math, let’s say that the sale of the ranch puts $30 million into the foundation coffers,” he adds. “Five percent of $30 million means that $1.5 million would be distributed throughout the local community. That’s money for search and rescue, rural fire departments, that sort of thing.”

The conservation easement stipulates that half of the property is immune to development or subdivision, thereby ensuring that Strand’s conservationist vision will endure. “This truly is a magnificent property,” Bjelland says. “The easement preserves it as an operating cattle concern with contiguous, open space, and the foundation reinvests Leroy’s estate into the community.”

Kendall Van Dyk, of the Montana Land Reliance, concurs. “Leroy Strand had a vision for what he wanted up there, and the Land Reliance has a very positive relationship with the foundation,” he says. “My sense is that the foundation is pretty community-minded, and will be selective in who buys the ranch.” Van Dyk explains that the ranch is much more than a cattle operation. “That area holds world-class elk and upland bird habitat.” He also notes that the conservation easement does not provide for public access, although Square Butte itself is public land.

Lennie McDonald, who worked for Strand on the ranch and is now on the foundation’s board of directors, extols the virtues of Strand’s conservation ethic, but also his acumen in improving the operation. “This ranch is so well-developed and its watering systems so streamlined, that really only two people could run the ranch for the most part,” he says. “You’d have to hire some hands for some aspects of the operation, but even moving the cattle around is mostly a matter of controlling the water — the cattle will move on their own to the water.” McDonald also points out that the hay itself is all native grass.

THE CRAGGY PEAKS OF THE MODEST HIGHWOOD MOUNTAINS OFFER THE ONLY ALPINE RELIEF IN THE VICINITY.

Strand’s life spanned eight decades of the 20th century, and a decade and a half of the 21st. Throughout that time, he witnessed incredible changes to the agricultural and economic climate in Montana. In creating the Strand Foundation, he sought to preserve the best aspects of a classic large cattle ranching operation, and at the same time to ensure that the surrounding community — of which he had been an exuberant member since he moved west from Iowa in 1967 — would continue to benefit from his estate. The next chapter in the Strand Ranch legacy is destined to be a great one.